The Invisible Loops That Are Killing Your Electronics

Introduction: The Hidden World of Your Circuit Board

If you've ever worked with electronics, you've likely encountered the ghost in the machine: the mysterious noise, the unpredictable behavior, the design that works perfectly on the bench but fails spectacularly at an EMC compliance lab. These frustrating problems often seem to come from nowhere, defying the simple, predictable rules of electricity we all learned.

The truth is, the neat diagrams of a battery, a switch, and a resistor from our textbooks don't tell the whole story. In the high-speed world of modern electronics, electricity behaves in strange, non-obvious ways. Current doesn't just flow; it calculates, it concentrates, and it radiates. Understanding how it really moves is the difference between a frustrating redesign and a successful product launch.

Fortunately, you don't need a degree in theoretical physics to master these concepts. The most impactful of these principles can be distilled into a few key, counter-intuitive truths. By learning to see the invisible loops and paths that exist on every circuit board, you can transform your design process from a game of chance into an act of precision engineering.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1. Current Has a Split Personality: The Path of Least Resistance vs. Inductance

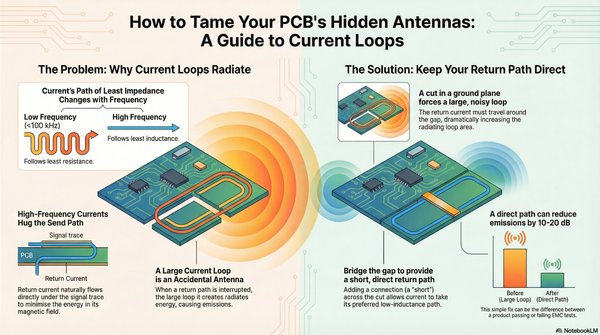

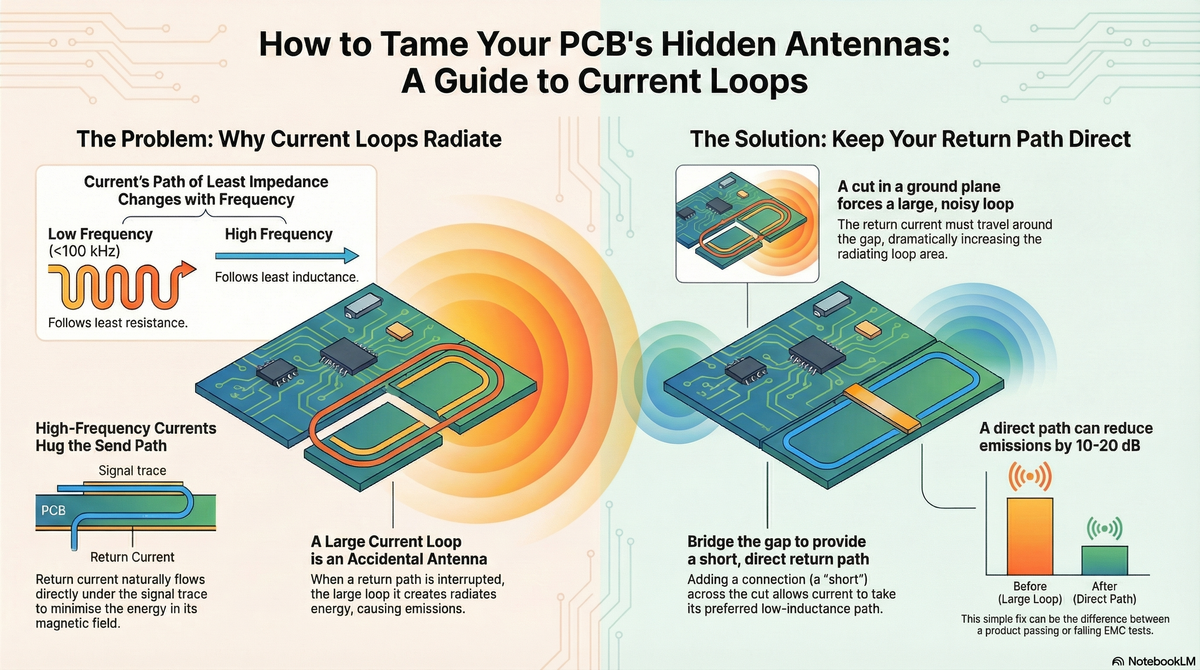

We're often taught that electricity follows the path of least resistance. While true, that's only half the story. The full principle is that current always takes the path of least impedance, and impedance has two components: resistance and inductance. Which one dominates depends entirely on frequency.

The surprising reality is that current's "preference" changes dramatically as frequency increases. This is because nature always seeks to minimize energy. At low frequencies, the energy used to overcome resistance is the main factor, so current follows the path of least resistance. At high frequencies, however, the energy stored in the magnetic field—which is related to inductance—becomes the dominant factor. To minimize this energy, current will change its path to create the smallest possible loop area, thereby minimizing inductance. An EMC instructor compared this to a water droplet, which always assumes a spherical shape to minimize the energy in its surface tension.

"...at DC and low frequency say for example under a hundred kilohertz or there abouts currents take the path of least resistance and high frequency say above approximately 100 kilohertz current prefers to take the path of least inductance..."

This is a critical distinction. As almost every modern circuit involves high-frequency switching, designers are constantly operating in a realm where controlling inductance—the property related to the magnetic field created by a current loop—is far more important than controlling simple resistance.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

2. The Return Path Isn't a Diffuse Flood; It's a Shadow

A common misconception, especially for boards with a solid ground plane, is that the return current spreads out evenly across the plane on its way back to the source. It seems logical that the current would take advantage of the massive, low-resistance copper area available. In reality, high-frequency current is much more disciplined.

A simulation detailed in a paper by Dr. Marco Klinger shows this behavior vividly. At a very low frequency of 10 Hz, the return current is spread out. But as the frequency increases to 1 kHz, 10 kHz, and finally 100 kHz, the return current path constricts itself until it flows in a tight, concentrated "shadow" directly underneath the primary signal trace.

This happens because a tight path directly under the signal trace minimizes the total area of the current loop, thereby minimizing the loop's inductance—the path of least impedance at high frequencies. When this natural return path is broken by a gap or cut in the ground plane, the current is forced to make a long detour. This creates a large loop that acts as an efficient antenna, radiating noise. Worse, it creates a shared path for other signals crossing the same gap, leading to increased crosstalk. A demonstration showed that with a large cut in the ground plane, radiated emissions were significant. However, when two buttons—one a direct short, the other capacitively coupled—were pressed to let the current bypass the loop, the emissions harmonics would "drop off significantly."

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

3. A Tiny "Common-Mode" Leak Can Be More Damaging Than a "Differential-Mode" Flood

Not all currents on your board are created equal. For the purpose of controlling emissions, we can think of them in two categories:

- Differential-Mode: These are the useful currents we want. They flow in a defined loop from a source, through a load, and back again, making our circuits work. They are associated with less-efficient loop antennas.

- Common-Mode: These are unwanted "stray" currents that escape the intended path. They flow together in the same direction on external cables (like power or USB cords) and return via some unintended path, like earth ground. This turns the entire cable into a highly efficient dipole antenna.

The most astonishing takeaway is the disproportionate impact of these two current types. Because the underlying physics makes dipole antennas far more effective radiators at frequencies below 1 GHz, common-mode currents are often the primary cause of EMC failures, even when they are thousands of times smaller than the circuit's functional differential-mode currents.

"...an excitation frequency of say a hundred megahertz with a common mode current in the order of micro amps that's likely to cause more trouble in terms of emissions than a differential mode current in in the order of milliamps at the same frequency..."

This is why controlling tiny, seemingly insignificant stray currents on I/O cables, chassis connections, and power cords is absolutely critical for passing emissions testing. A few microamps of common-mode noise can radiate far more effectively than milliamps of the signal current you're actually trying to manage.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

4. In a Power Supply, One Specific Loop Is the Supervillain

Nowhere are these principles more critical than in a switch-mode power supply (SMPS). In any switching circuit, there is one loop that carries current with the highest rate of change (di/dt). This is known as the "critical current loop," and it is the primary source of radiated and conducted noise. Minimizing its size is paramount.

A case study comparing two revisions of a Texas Instruments power supply board provides a stunning example of this principle in action.

- Rev A: The initial 2-layer board layout resulted in a critical current loop with a length of approximately 38 millimeters.

- Rev B: This revision implemented several key improvements. Designers moved to a 4-layer board, added a snubber network to damp ringing, and buried the high-speed gate drive signal on an internal layer for shielding. Crucially, they optimized component placement, more than halving the critical current loop length to just 18 millimeters. This simple change reduced the physical loop area by more than a factor of four.

The measured results of these holistic optimizations were staggering. Compared to the noisy Rev A board, the Rev B board showed a massive reduction in conducted emissions, with improvements of "10, 20, 30 dB" at higher frequencies.

In practical terms, this combination of layout and schematic enhancements—the most dramatic of which was shrinking the critical loop—was the difference between a design that would fail compliance and one that would "sail through." In fact, TI engineers confirmed the Rev B design is "compliant with European standards for sis per 22 as well," saving thousands of dollars in redesign costs and weeks of engineering time.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Conclusion: See the Invisible, Control the Unpredictable

Mastering EMC and creating robust electronic designs isn't about memorizing complex equations; it's about learning to visualize the invisible. It’s about seeing the high-frequency current loops that are inherent in every circuit and understanding that at modern switching speeds, you are not just designing a circuit—you are designing a system of miniature antennas. By minimizing the area of these loops, you minimize their ability to radiate and cause problems.

The key is to shift your thinking from simple resistance to high-frequency impedance, from diffuse return paths to concentrated shadows, and from large signal currents to tiny, destructive common-mode currents. Once you start seeing your layout through this lens, you gain control over the unpredictable behavior that plagues so many designs.

Now that you know how current really behaves, what's the first invisible loop you'll hunt for in your next design?