try this out

Power architecture rarely begins with a blank whiteboard and a stroke of genius. In real organizations, it begins with something far less romantic and far more binding: requirements.

1. Everything starts with the requirement

The requirement document is the gravitational center of the entire architecture effort. It tells us:

- Which standards must be met

- Electrical limits, efficiency targets, derating rules

- Environmental constraints like temperature, altitude, lifetime

- EMC, safety, reliability, and sometimes cost ceilings

At this stage, architecture is less about creativity and more about interpretation. Two engineers can read the same requirement and arrive at very different architectures depending on what risks they choose to surface early.

2. Reuse before reinventing

The next move is rarely “design from scratch.”

Most organizations ask a pragmatic question:

Have we already built something that does roughly this?

Existing circuits from previous programs are reviewed to see if they can deliver the same function. Sometimes they fit almost perfectly. Sometimes they need:

- Component updates due to obsolescence

- Re-rating for different power levels

- Re-analysis for a new operating envelope

Reuse is powerful, but it carries inherited assumptions. Many of those assumptions are undocumented and only reveal themselves later.

3. Engage suppliers early

Once a candidate architecture takes shape, engineers usually reach out to leading IC suppliers.

This is where the landscape can shift:

- New controllers with integrated protection

- Digital power features that reduce external circuitry

- Better current sensing, telemetry, or fault handling

Sometimes a single IC advancement collapses an entire block diagram. Sometimes it adds complexity disguised as elegance. Supplier discussions help map what is possible, not what is proven.

4. Simulate to validate intent

With circuits selected, simulations begin:

- Steady-state performance

- Transient response

- Control loop stability

- Worst-case corners

Simulation answers an important question:

Does this architecture meet the requirements in principle?

But simulation is only as honest as the assumptions behind it. Parasitics, layout-dependent effects, and temperature coupling are often simplified or ignored entirely at this stage.

5. Eval boards and early hardware

To move faster, teams often buy evaluation boards, then modify them:

- Change power stages

- Adjust feedback networks

- Swap magnetics or sense elements

Development testing begins. Confidence grows. The architecture looks viable. Schedules tighten.

And this is where reality starts pushing back.

6. Where assumptions quietly break

Many of the early assumptions made to move quickly turn out to be incomplete or wrong.

Thermal performance is a classic example.

You cannot truly understand thermal behavior without an accurate loss model. And accurate loss modeling is difficult without:

- Real switching waveforms

- Temperature-dependent device data

- Layout-aware parasitic

As a result, early thermal estimates are often optimistic.

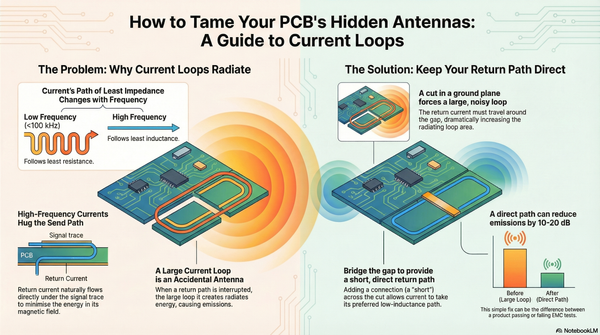

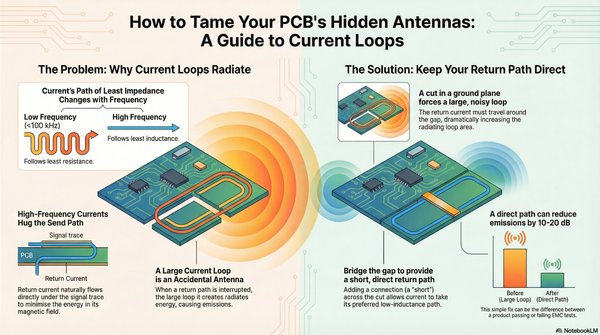

EMC performance is another late surprise.

Simulation rarely captures:

- Common-mode noise paths

- Coupling through mechanical structures

- The impact of cable routing and grounding schemes

What looked clean on the bench can become noisy in a system-level test environment.

7. De-risking is about timing, not elimination

The goal of power architecture is not to eliminate risk. That is unrealistic.

The real goal is to surface the right risks early, when they are still cheap to fix:

- Question inherited designs, even successful ones

- Be explicit about assumptions in simulations

- Treat eval boards as learning tools, not validation tools

- Pull thermal and EMC thinking forward, even if imperfect

Good power architects are not the ones who avoid surprises entirely. They are the ones who make sure surprises happen early, not during qualification.